You’ve been caring for your aging parent for months, maybe years. At first, you managed the doctors’ appointments, medication schedules, and daily needs with determination. But lately, something has shifted. You feel numb when your challenged parent shares their struggles. You snap at small inconveniences. You’re exhausted in a way that sleep doesn’t fix.

This isn’t weakness; it’s compassion fatigue (sometimes called vicarious traumatization), and it affects both healthcare workers and family caregivers.

While professional caregivers have some institutional support, family caregivers often suffer in silence, unaware that their emotional exhaustion has a name and, more importantly, that recovery is possible.

What Is Compassion Fatigue in Caregiving?

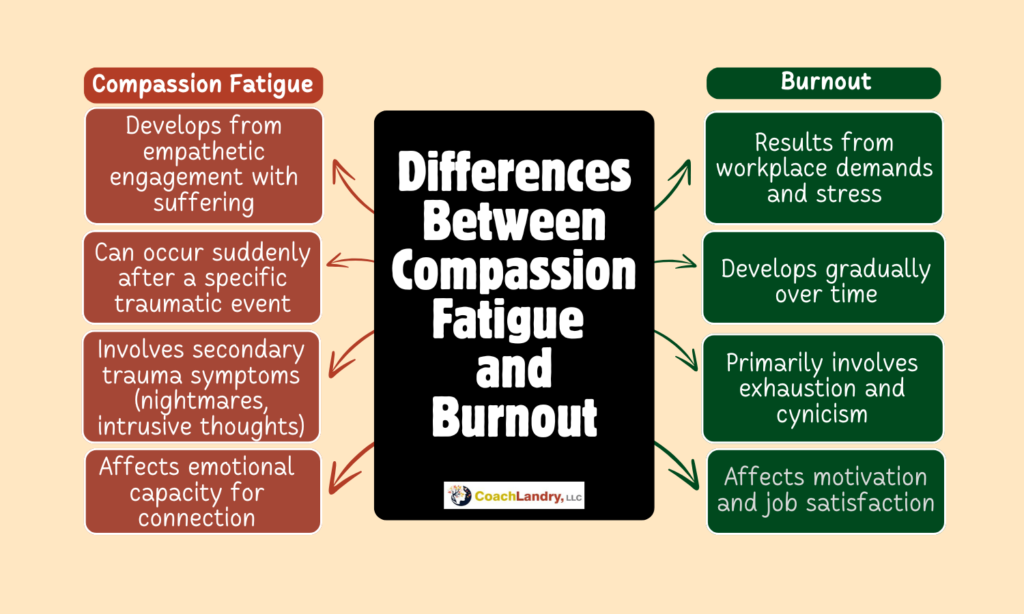

Compassion fatigue is the emotional and physical exhaustion that develops from prolonged exposure to another person’s suffering. Unlike burnout, which results from workplace stress, compassion fatigue stems from empathetic engagement with someone experiencing trauma, pain, or chronic illness.

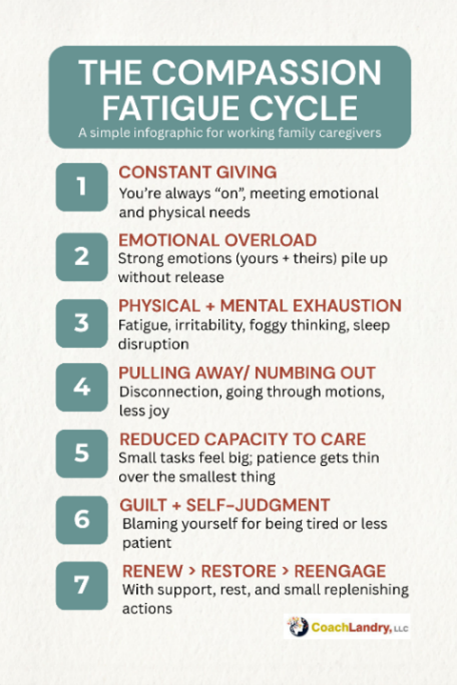

The Three Core Components:

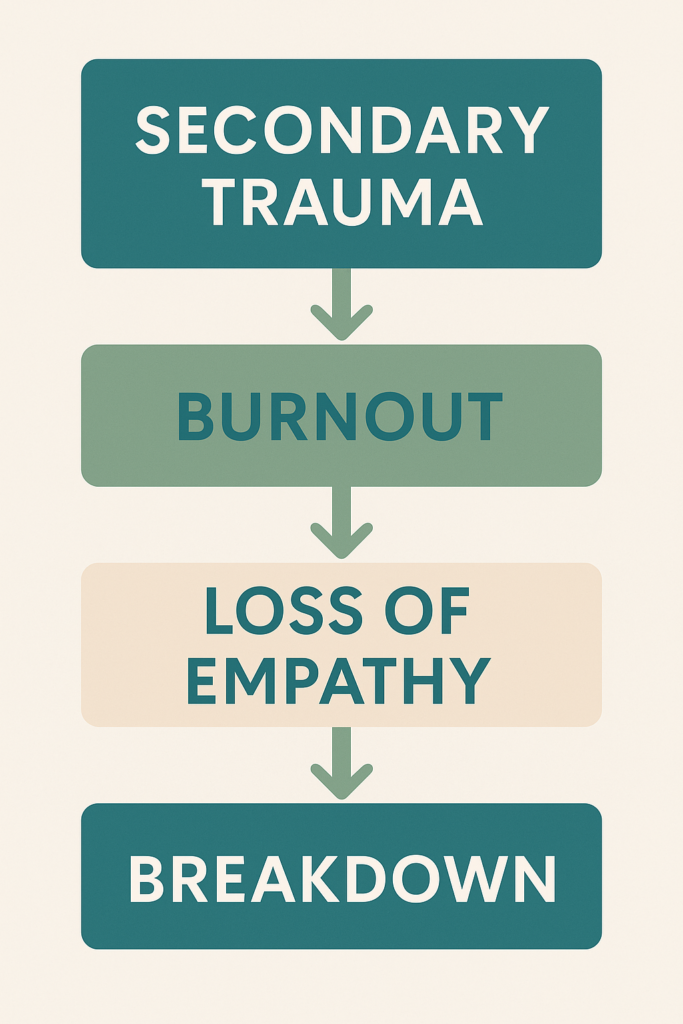

1. Secondary Traumatic Stress: You absorb the emotional pain of the person receiving your care. Their anxiety becomes your anxiety. Their suffering infiltrates your thoughts even when you’re apart.

2. Burnout: The chronic stress of caregiving depletes your physical and emotional resources. Tasks that once felt manageable now feel impossible.

3. Loss of Empathy Perhaps most distressing: you stop feeling. The emotional numbness that develops isn’t callousness; it’s your nervous system attempting to protect you from overwhelming pain.

How Compassion Fatigue Differs from Burnout:

| Compassion Fatigue | General Burnout |

| Develops from empathetic engagement with suffering | Results from workplace demands and stress |

| May occur suddenly after a specific traumatic event | Develops gradually over time |

| Involves secondary trauma symptoms (nightmares, intrusive thoughts) | Primarily involves exhaustion and cynicism |

| Affects emotional capacity for connection | Affects motivation and job satisfaction |

The Science Behind Secondary Trauma in Caregiving

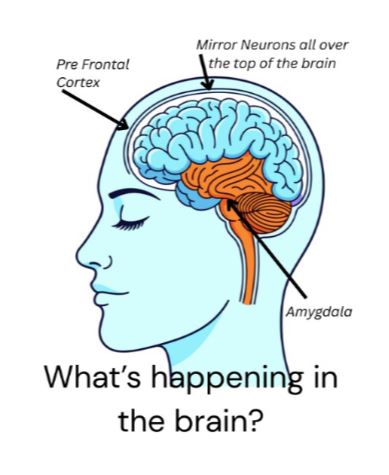

When you witness a loved one’s pain repeatedly, your brain processes this experience similarly to direct trauma. Neuroscience research shows that empathy activates many of the same brain regions as personal experience.

What Happens in Your Brain:

Mirror Neurons Activation: These specialized brain cells fire both when you experience something harsh and when you witness someone else experiencing it. When your loved one winces in pain, your brain registers a version of that pain.

Amygdala Hyperactivation: As a result, the brain’s

threat-detection system becomes hypersensitive.

You’re constantly scanning for the next crisis,

maintaining a state of hypervigilance that exhausts

your nervous system.

Prefrontal Cortex Impairment: Chronic stress

impairs the brain region responsible for emotional

regulation and decision-making. This explains why

you might find yourself snapping at minor

frustrations or struggling with simple decisions.

The Physiological Impact:

Compassion fatigue isn’t “just” emotional. It also manifests physically in the body:

- Elevated cortisol levels lead to weakened immune system function

- Disrupted sleep patterns (difficulty falling asleep/staying asleep) can lead to brain fog

- Digestive issues, headaches, and muscle tension complicate things further

- Changes in appetite (eating too much/too little), causing additional energy loss

- Increased susceptibility to illness due to the weakened immune system

Recognizing Critical Compassion Fatigue

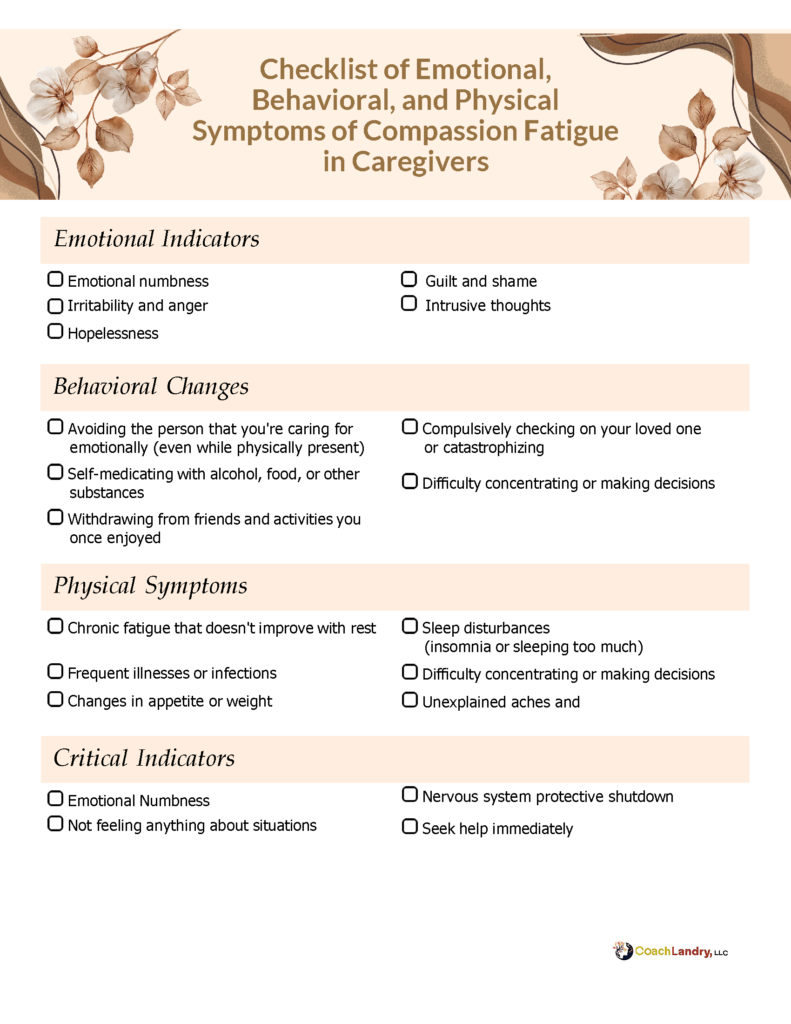

Emotional Warning Signs:

- Emotional numbness: You no longer feel sadness, joy, or empathy

- Irritability and anger: Small frustrations trigger disproportionate emotional

reactions - Hopelessness: You can’t see a path forward or envision improvement

- Guilt and shame: You feel inadequate despite doing your best

- Intrusive Thoughts: Images/memories of your family member’s suffering intrude when you’re trying to rest

Behavioral Changes:

- Avoiding the person that you’re caring for emotionally (even while physically present)

- Self-medicating with alcohol, food, or other substances

- Withdrawing from friends and activities you once enjoyed

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- Compulsively checking on your loved one

Physical Symptoms:

- Chronic fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest

- Frequent illnesses or infections

- Sleep disturbances (insomnia or sleeping too much)

- Changes in appetite or weight

- Unexplained aches and pains

Critical Indicator: If you’re

experiencing emotional numbness,

where you genuinely don’t feel

anything about situations that

would normally move you, it

suggests your nervous system has

shifted into protective shutdown

mode. This requires immediate

attention.

Building Emotional Resilience

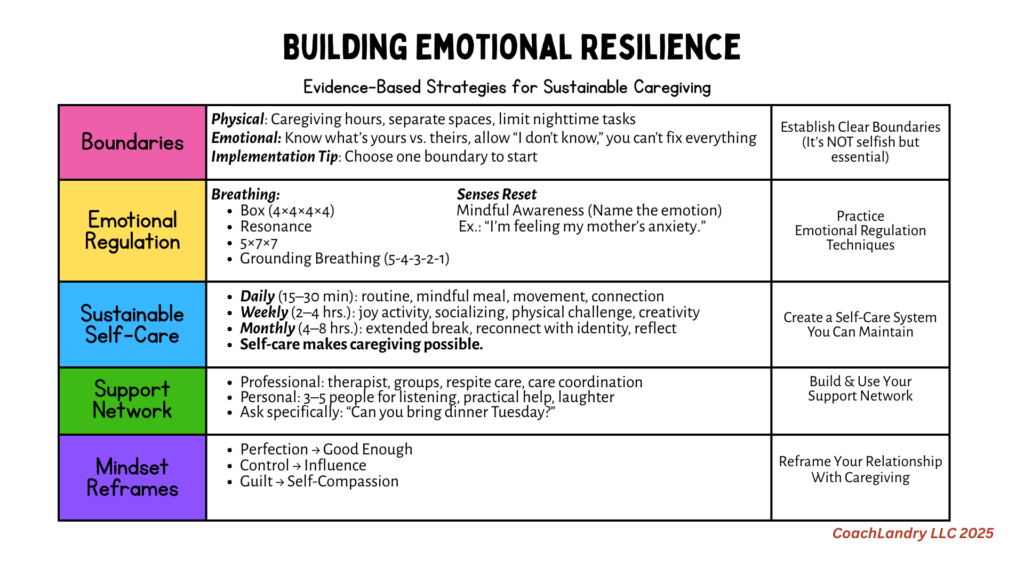

Evidence-Based Strategies: Resilience isn’t about “toughing it out” or “pushing through”. It’s about developing sustainable practices that allow you to continue caring without destroying yourself in the process.

- Establish Clear Boundaries: Boundaries aren’t selfish; they’re essential for sustainable caregiving.

A. Physical Boundaries

• Designate specific caregiving hours when possible

• Create physical space for yourself that’s separate from caregiving duties

• Limit nighttime caregiving tasks unless medically necessary

B. Emotional Boundaries:

• Recognize where your responsibility ends and your loved one’s agency begins

• Allow yourself to say “I don’t know” or “I need to think about that”

• Accept that you cannot fix everything

Practical Implementation: Start with one small boundary. For example: “I won’t check my phone during dinner” or “Sundays from 10-12 are my time to [specific self-care activity].” - Practice Emotional Regulation Techniques

Box Breathing (4-4-4-4 Method): When you feel overwhelmed:

• Inhale for 4 counts

• Hold for 4 counts

• Exhale for 4 counts

• Hold empty for 4 counts

• Repeat 4-5 cycles

This activates your parasympathetic nervous system, interrupting the stress response.

Grounding Techniques: Use the 5-4-3-2-1 method for dissociation / overwhelmed feelings:

• Name 5 things you can see

• 4 things you can touch

• 3 things you can hear

• 2 things you can smell

• 1 thing you can taste

Mindful Awareness: Notice when you’re absorbing your loved one’s emotions without trying to fix or change this awareness. Simply naming what’s happening, “I’m feeling my mother’s anxiety right now”. creates psychological distance. - Develop a Sustainable Self-Care System

Self-care isn’t optional. It’s the foundational action that makes caregiving possible.Daily Non-Negotiables (15-30 minutes):

- Morning routine before caregiving begins (even 10 minutes)

- Eat one meal slowly and mindfully

- Brief physical movement (walk, stretch, gentle yoga)

- Connection with someone outside the caregiving relationship

Weekly Restoration (2-4 hours):

- Activity that brings you joy (not just rest)

- Social connection beyond discussing caregiving

- Physical activity that challenges you appropriately

- Creative expression (writing, art, music, gardening)

Monthly Reset (4-8 hours):

- Extended time away from caregiving environment

- Activity that connects you to your pre-caregiver identity

- Reflection on what’s working and what needs adjustment

Important: If you’re thinking, “I don’t have time for this,” that’s precisely why you need it.

Self-care isn’t a reward for when everything else is done; it’s what makes “everything else” possible. -

Build Your Support Network

Caregiving was never meant to be solitary.

Professional Support:- Therapist specializing in caregiver stress or trauma

- Certified coach who was/is a caregiver and has training to back it up

- Caregiver Group coaching (online small caregiver group sessions)

- Support groups (online or in-person) with other caregivers

- Respite care services (investigate options in your area)

- Care coordination through social services

Personal Support:

-

-

- Identify 3-5 people you can reach out to for specific types of support:

- Someone who will listen without trying to fix

- Someone who can provide practical help (errands, meals)

- Someone who helps you laugh and remember who you are beyond caregiving

- Identify 3-5 people you can reach out to for specific types of support:

-

Ask specifically for help: Instead of “Can you help?” try “Could you bring dinner onTuesday?” or “Would you sit with Dad while I go to my doctor’s appointment on Thursday at 2 PM?”5

-

Reframe Your Relationship to Caregiving

From Perfectionism to “Good Enough”: You don’t have to be the perfect caregiver. You must be a sustainable one. Good enough, delivered consistently, is better than excellence followed by collapse.

From Control to Influence: You cannot control your loved one’s illness progression or emotional state. You can influence their comfort, safety, and quality of life. Accepting this difference reduces the crushing weight of responsibility.

From Guilt to Self-Compassion: Notice your self-talk. Would you speak to a friend the way you speak to yourself? When you catch harsh self-judgment, pause and ask: “What would I say to someone I love in this situation?”

Protective Strategies for Empathetic Caregivers

High empathy is both your strength and your vulnerability. Here’s how to honor your empathy while protecting your well-being:

1. Practice Compassionate Detachment

This isn’t about caring less. It’s about caring wisely.

Visualization Exercise: Imagine a glass wall between you and your loved one’s suffering. You can see it, acknowledge it, and respond to it, but it doesn’t penetrate your body. Their pain is theirs to carry; your role is to support, not to absorb.

2. Distinguish Between Empathy and Responsibility

Empathy: “I understand my mother is frightened by her diagnosis.”

Over-responsibility: “I must eliminate all her fear and anxiety.”

The first is healthy. The second is impossible and will destroy you.

3. Monitor Your Emotional Exposure

Track your emotional state using a simple 1-10 scale daily. If you notice you’re consistently below 5, this is data telling you that your current approach isn’t sustainable.

Develop a practice that marks the shift between caregiving and personal time:

- Change clothes

- Brief shower or face washing

- Five-minute walk

- Listen to a specific song

- Light a candle

These rituals signal to your nervous system that you’re shifting roles.

Recovery and Healing: The Path Forward

If you’re already experiencing compassion fatigue, recovery is possible. It requires intentional action and often professional support.

Immediate Steps:

- Acknowledge the Reality: Name what’s happening: “I’m experiencing compassion fatigue.” This isn’t weakness—it’s a normal response to abnormal stress.

- Seek Professional Support: A therapist trained in caregiver stress, trauma, or EMDR can help process the secondary trauma you’ve absorbed.

- Arrange Respite Care Immediately: Even 24-48 hours away can begin the recovery process. This isn’t about abandonment. It’s about essential maintenance.

Long-term Recovery:

Therapy Approaches That Help:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for stress management

- EMDR for processing secondary trauma

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for values clarification

- Somatic experiencing releasing stored stress

Coaching Approaches That Help

- Appreciative Inquiry about feelings processing

- Providing a non-judgmental, safe-haven environment to be seen

- Motivational Interviewing allows you to be heard by your coach and your subconscious

Rebuilding Your Capacity: Recovery isn’t linear. Some days feel like progress; others feel like regression. This is normal. Healing from compassion fatigue typically takes 3-6 months of consistent intervention, but improvements often appear within weeks.

When to Seek Professional Help

Seek immediate professional support if you’re experiencing:

- Persistent thoughts of harming yourself

- Complete emotional numbness lasting more than two weeks

- Inability to function in daily activities

- Substance abuse as a coping mechanism

- Thoughts of harming your loved one (intrusive thoughts are different from intent, but both require professional support)

Remember: Seeking help isn’t a sign that you’ve failed as a caregiver. It’s a sign that you’re a human being under extreme stress who deserves support.

Frequently Asked Questions About Compassion Fatigue in Caregiving

Understanding Compassion Fatigue

Q: What exactly is compassion fatigue, and how is it different from just being tired?

A: Compassion fatigue is the emotional and physical exhaustion that develops from prolonged exposure to another person’s suffering. While regular fatigue improves with rest, compassion fatigue persists even after sleeping.

It’s characterized by three core components: secondary traumatic stress (absorbing your loved one’s emotional pain), burnout (depletion from chronic caregiving demands), and loss of empathy (emotional numbness as your nervous system self-protects). If you find yourself feeling nothing when your loved one shares their struggles, or if their anxiety has become your anxiety even when you’re apart, you’re experiencing compassion fatigue, not simple exhaustion.

Q: Can family caregivers really get compassion fatigue, or is it just something healthcare professionals experience?

A: Family caregivers experience compassion fatigue at nearly identical rates to healthcare professionals. In fact, family caregivers may be more vulnerable because the emotional intensity of caring for someone you love can be overwhelming, you typically have less institutional support, fewer boundaries between “work” and “home,” and often carry guilt that prevents you from taking necessary breaks.

The difference is that professional caregivers usually have some access to debriefing, supervision, and mental health resources, while family caregivers often suffer in isolation without even knowing their exhaustion has a name.

Q: How long does compassion fatigue last? Will I ever feel like myself again?

A: Recovery from compassion fatigue typically takes 3-6 months with consistent, intentional intervention, including professional therapy, exposure to heart-based coaching to help establish boundaries, regular self-care practices, rebuilding your sense of self, and respite care. However, many caregivers notice meaningful improvement within 2-3 weeks of implementing even basic support systems.

The timeline depends on several factors: how long you’ve been experiencing symptoms, the severity of your burnout, whether you can access respite care, and, if you’re receiving professional mental health support. The critical thing to understand is this: recovery is possible, but it requires active intervention. Compassion fatigue doesn’t resolve simply by “pushing through” or “toughing it out.”

Q: Is compassion fatigue the same thing as depression or PTSD?

A: Compassion fatigue shares symptoms with both depression and PTSD, but it’s a distinct condition. Unlike clinical depression, compassion fatigue is specifically triggered by empathetic engagement with someone else’s trauma and suffering.

Unlike PTSD, which develops from direct personal trauma, compassion fatigue results from indirect trauma exposure, such as witnessing and absorbing another person’s pain over time. However, untreated compassion fatigue can develop into clinical depression or a condition called Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder (very similar to PTSD).

Mental health professionals may diagnose you with secondary traumatic stress if you’re experiencing intrusive thoughts about your loved one’s suffering, hypervigilance, emotional

numbing, and sleep disturbances. This is why professional evaluation is important. The symptoms overlap, but treatment approaches may differ.

Q: What causes some caregivers to develop compassion fatigue while others don’t?

A: Several factors can increase vulnerability to compassion fatigue. High empathy, for example, puts caregivers at greater risk of absorbing a loved one’s emotional pain. Other risk factors include caring for someone with a progressive or terminal illness (ongoing grief), lack of respite or family support, a personal history of trauma, perfectionist tendencies, difficulty setting boundaries, isolation from friends and usual activities, caring for someone whose personality has changed (such as with dementia or brain injury), and limited access to mental health support. Importantly, developing compassion fatigue does not mean you are weak. More often, it means you care deeply and have been carrying an unsustainable burden without enough support.

Recognizing the Signs

Q: What are the earliest warning signs of compassion fatigue I should watch for?

A: The earliest warning signs are often subtle changes in your emotional responses. These may include feeling emotionally numb or disconnected when your loved one shares their pain (when you used to feel moved). Possible additional warning signs may include disproportionate irritability over minor inconveniences, persistent worry about your loved one even when apart, and changes in sleep patterns (such as trouble falling asleep, waking frequently, or sleeping excessively).

You might also avoid emotional conversations with the person you care for, even while remaining physically present, or experience physical symptoms like frequent headaches, digestive issues, or catching every cold. The most concerning sign is emotional numbness. If you notice you truly don’t feel anything in situations that would normally move you, it may mean your nervous system has entered protective shutdown mode and needs immediate professional attention.

Q: How do I know if what I’m experiencing is compassion fatigue or just normal caregiver stress?

A: Normal caregiver stress typically improves with a good night’s sleep, a weekend break, or stress-reduction activities. Compassion fatigue persists regardless of rest and includes specific secondary trauma symptoms. Ask yourself these questions: Do I have intrusive thoughts or mental images of my loved one’s suffering when I’m trying to relax or sleep?

Have I lost the capacity to feel empathy or emotional connection, not just with the person I’m caring for, but with others in my life? Do I feel a sense of hopelessness about the future that doesn’t lift even during good moments? Am I experiencing physical symptoms (frequent illness, unexplained pain, digestive issues) that have appeared since becoming a caregiver?

If you answered yes to two or more, you’re likely experiencing compassion fatigue rather than typical stress, and professional support would be beneficial.

Q: Can you have compassion fatigue even if you still love the person you’re caring for?

A: Absolutely yes. This is one of the most painful and misunderstood aspects of compassion fatigue. You can deeply love someone while simultaneously feeling emotionally numb to their daily struggles. You can be completely committed to their care while also feeling resentful about the demands.

Compassion fatigue doesn’t erase love; it depletes your emotional capacity to express that love in the ways you once did. Many caregivers experiencing compassion fatigue describe their feelings as “disconnected” from their loved one, like they’re “going through the motions” of care without the emotional warmth that once was there. This creates enormous guilt.

You think you’re becoming a “bad person” or “heartless caregiver.” However, you’re experiencing a physiological response to prolonged trauma exposure. Your love hasn’t disappeared; your nervous system is trying to protect you from overwhelming pain by shutting down emotional responsiveness.

Q: What’s the difference between compassion fatigue and caregiver burnout?

A: While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they have important differences. Caregiver burnout develops gradually over time from chronic, intense stress from the endless to-do lists, physical exhaustion, lack of appreciation, and feeling like your own life is on hold. Burnout primarily causes exhaustion, cynicism, and a reduced sense of accomplishment.

Compassion fatigue, by contrast, develops specifically from empathetic engagement with suffering and can appear suddenly after a particular traumatic event (like witnessing your care recipient’s medical crisis). Compassion fatigue includes secondary trauma symptoms such as nightmares, intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, and emotional numbness. You can experience both simultaneously.

Burnout from the practical demands of caregiving, plus compassion fatigue from the emotions of witnessing suffering. The treatment approaches overlap but aren’t identical.

Q: Is feeling angry or resentful toward the person I’m caring for a sign of compassion fatigue?

A: Anger and resentment can be symptoms of compassion fatigue, particularly when they feel disproportionate or when you barely recognize yourself in these reactions. However, it’s important to distinguish between different types of anger. Occasional frustration when your mom asks the same question for the fifteenth time, or resentment that you can’t travel like your siblings.

These are normal human emotions in challenging circumstances. Compassion fatigue-related anger tends to be more pervasive, more intense, and often accompanied by guilt and shame. You might snap over tiny things, feel rage that frightens you, or experience persistent resentment that doesn’t ease even during pleasant moments.

If you’re worried about your anger, that self-awareness is a positive sign. It means you recognize something is wrong and you’re seeking to understand it rather than acting destructively.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

Q: Can compassion fatigue make me physically sick?

A: Yes, compassion fatigue has well-documented physical health consequences. Chronic exposure to secondary trauma keeps your body in a prolonged stress response, elevating cortisol levels and triggering your sympathetic nervous system. This physiological state weakens your immune system, making you significantly more susceptible to infections, colds, and flu.

Physical manifestations of compassion fatigue include frequent illnesses that seem to come one after another, chronic digestive problems (IBS symptoms, stomach pain, nausea), persistent headaches/migraines, muscle tension, especially in the neck, shoulders, and jaw, eating much more or much less than normal, and sleep disturbances. Long-term, untreated compassion fatigue is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, autoimmune conditions, and chronic pain syndromes. Your body quite literally keeps the score of emotional traumas. Physical health cannot be separated from mental and emotional well-being.

Q: Why can’t I sleep even though I’m completely exhausted all the time?

A: The sleep disturbances associated with compassion fatigue occur because your nervous system remains in hypervigilant mode, constantly scanning for the next crisis, even when you’re trying to rest. Your brain has learned that danger (your loved one’s medical emergency, fall, wandering) could happen at any moment, so it resists fully relaxing into deep sleep. Additionally, intrusive thoughts about your loved one’s suffering may surface precisely when you’re trying to fall asleep.

Elevated cortisol levels then disrupt your natural sleep-wake cycle. The exhaustion-insomnia paradox is one of the most frustrating aspects of compassion fatigue. Your body desperately needs rest, but your nervous system won’t permit it.

Q: I’ve started having nightmares about something bad happening to my loved one. Is this normal?

A: Nightmares and intrusive imagery about your loved one’s suffering or potential harm are classic symptoms of secondary traumatic stress, a core component of compassion fatigue. These are your brain’s attempts to process and make sense of the trauma you’ve witnessed or the constant anticipatory fear you’re carrying. The nightmares may replay actual events you’ve witnessed (your father’s fall, your mother’s panic attack, a frightening medical emergency) or create worst-case scenarios your mind is trying to prepare for in advance.

This is your brain operating in trauma-processing mode. While experiencing these nightmares indicates significant psychological stress, they’re a documented response to caregiver trauma. However, persistent nightmares warrant professional support.

Therapies like EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) are particularly effective for processing trauma-related sleep disturbances.

Getting Help and Support

Q: When should I seek help for compassion fatigue, and what type of help should I look for?

A: The earliest warning signs are often subtle changes in your emotional responses. You may notice emotional numbness or disconnection when your loved one shares their pain, feelings that once moved you no longer do. Other signs include disproportionate irritability over minor inconveniences, persistent worry about your loved one even when apart, and changes in sleep patterns, such as difficulty falling asleep, frequent waking, or excessive sleep.

You might also find yourself avoiding emotional conversations with the person you care for, even while remaining physically present, or experiencing frequent headaches, digestive issues, or catching every cold. The most concerning sign is emotional numbness: if you realize you truly don’t feel anything in situations that would normally affect you, your nervous system may have shifted into protective shutdown mode and requires immediate professional attention.

Q: How do I find a support group for caregivers experiencing compassion fatigue?

A: This certified coach writing this blog offers online group coaching for caregivers that addresses emotional well-being and includes a caregiver community that is open for discussions at all hours. For advanced compassion fatigue resources, several national organizations offer both online and in-person caregiver support groups, many specifically addressing compassion fatigue and emotional burnout.

Start with: Family Caregiver Alliance (caregiver.org) offers online support groups and local connections. Caregiver Action Network (caregiveraction.org) provides peer support and education programs. ARCH National Respite Network (archrespite.org) connects you with respite services and support.

Alzheimer’s Association (alz.org) hosts support groups specifically for dementia caregivers dealing with grief and trauma. Cancer Support Community (cancersupportcommunity.org) offers groups for cancer caregivers. Well Spouse Association (wellspouse.org) supports partners caring for chronically ill spouses. Additionally, many hospitals and senior centers host local caregiver support groups.

Q: What if I can’t afford coaching, therapy, or respite care?

A: Financial barriers are real, but several low-cost and free options exist. Many certified coaches, including the writer of this blog, offer scholarships or sliding-scale fees based on income for coaching to family caregivers experiencing financial distress. For therapy, many therapists offer sliding-scale fees based on income; community mental health centers provide services regardless of ability to pay.

Open Path Collective (openpathcollective.org) connects people with therapists offering $30-$80 sessions. Psychology Today’s therapist directory allows you to filter by insurance accepted and sliding scale availability. Some employers offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) that provide free confidential counseling.

For respite care, contact your local Area Agency on Aging (eldercare.acl.gov) for free or subsidized respite programs. Investigate whether your loved one qualifies for Medicaid

waiver programs that cover respite services. Reach out to faith-based organizations (churches, synagogues, mosques) that often have volunteer caregiving programs.

Join or create caregiver co-ops where families trade respite time. Explore adult day programs, which are often less expensive than in-home care. Check if local nursing or medical schools offer student-supervised respite as part of training programs.

Don’t let financial constraints prevent you from seeking help. Resources exist, though they may require some research to find.

Q: How do I talk to my family about needing more help without sounding like I’m complaining or can’t handle it?

A: Frame the conversation around sustainability rather than current failure. Use specific, concrete language: “To continue providing quality care for Mom long-term, I need to implement some support systems now.” Make direct requests instead of general pleas: “I need someone to stay with Dad every Tuesday from 2-5 pm so I can attend therapy appointments”.

Share facts rather than emotions initially: “I’ve been providing care for 18 months without a full day off, and research shows this level of caregiving without respite leads to serious health consequences for caregivers”. This gives family members objective information.

Educate them about compassion fatigue: “I’ve learned I’m experiencing something called compassion fatigue, which is a documented condition affecting many family caregivers. My therapist says I need regular breaks to continue caregiving safely.” Use “and” instead of “but”: “I love Mom, and I’m committed to her care, and I need us to create a sustainable plan together.”

If siblings are resistant, consider involving a neutral third party, like a social worker or therapist.

Q: What do I do if I’m having thoughts about harming myself or the person I’m caring for?

A: If you’re having thoughts of harming yourself or your loved one, whether these are intrusive thoughts you don’t intend to act on or active plans, you need immediate professional intervention. This is a mental health crisis, not a character failure. Immediately: Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988 (available 24/7,specifically trained in caregiver crisis situations).

Text HOME to 741741 for the Crisis Text Line if you prefer texting; call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room if you feel you cannot keep yourself or your loved one safe.

Contact your therapist if you have one, even outside regular hours. Most have emergency protocols.

Within 24 hours: Arrange emergency respite care through your Area Agency on Aging or a crisis respite program. Contact adult protective services to discuss temporary placement if needed. This is not abandonment, it’s safety planning.

Inform your physician about your mental health crisis. They can expedite mental health referrals and potentially prescribe short-term medication support. Understand this: Intrusive thoughts about harm are common in severe compassion fatigue and don’t mean you’re a dangerous person. They mean you’re in psychological distress, and your brain is overwhelmed. However, they absolutely require professional help to resolve safely.

Practical Strategies and Recovery

Q: What are the most effective immediate things I can do right now if I’m experiencing compassion fatigue?

A: Focus on implementation over perfection. Even small changes matter. Today, right now: Practice box breathing for 5 minutes (inhale 4 counts, hold 4, exhale 4, hold 4, repeat).

Call one person and ask for one specific form of help this week. Identify your “non-negotiable” self-care activity and schedule it on your calendar. Give yourself explicit permission to feel what you’re feeling without judgment.

This week: Make one appointment, coaching, therapy, regular doctor checkup, or consultation with Area Agency on Aging about respite. Establish one small boundary (e.g., “I don’t check caregiving-related messages after 8 pm”). Spend 15 minutes doing something purely for joy, not productivity. Tell at least one person you’re struggling with compassion fatigue.

This month: Research and join one caregiver support group (online counts). Schedule respite care even if it’s just for 3 hours. Write down what sustainable caregiving would look like for you.

Assess which tasks could be delegated, simplified, or eliminated. Remember, recovery from compassion fatigue requires consistent small actions over time, not one dramatic gesture. Start where you are, with what you can do today.

Q: How do I set boundaries without feeling like I’m abandoning my loved one?

A: Boundaries are the foundation that makes sustainable caregiving possible. Reframe boundaries as an act of love. You’re ensuring you can continue providing care long-term rather than collapsing from exhaustion.

Start with small, specific boundaries rather than sweeping changes. “I will not answer caregiving-related calls between 10 pm-7 am unless it’s a medical emergency” is more manageable than “I need my family to stop expecting so much from me.”

Communicate boundaries clearly and factually: “Going forward, I’ll be taking Sundays 10 am-12 pm for self-care activities. Here’s the contact information for [backup person] if you need something during that time.” Anticipate and plan for guilt. It will arise, and that doesn’t mean your boundary is wrong.

Remember that your loved one benefits more from a caregiver who sets boundaries and remains emotionally present than from one who martyrs themselves and eventually becomes numb, resentful, or ill. If you’re providing care that you genuinely cannot sustain for another 6 months at the current pace, boundaries aren’t optional. They’re necessary for everyone’s well-being.

Q: What’s the difference between self-care that helps compassion fatigue versus self-care that’s just a temporary band-aid?

A: Superficial self-care (bubble baths, shopping, occasional massage) provides temporary relief but doesn’t address the root causes of compassion fatigue. Meaningful self-care creates sustainable systems and addresses psychological needs.

Band-aid self-care: Isolated treats and activities, done irregularly when you’re at crisis point, focused on temporary escape or numbing, do not involve setting boundaries or asking for help, and leave the fundamental caregiving situation unchanged.

Sustainable self-care: Regular, scheduled activities embedded in your routine addressing both symptom relief and root causes. Sustainable self-care includes setting boundaries/redistributing responsibilities. It involves building support systems and community.

Activities here incorporate professional help (coaching, therapy, support groups). They create space for emotional processing, and honor rest as productive. Rest is not seen as “doing nothing.”

The self-care that addresses compassion fatigue isn’t about “treating yourself”. It’s fundamentally restructuring your approach to caregiving so it’s sustainable. This often means uncomfortable conversations, delegating control, accepting imperfection, and challenging social beliefs about what a “good caregiver” should sacrifice.

Q: How long should I expect the recovery process to take, and what does recovery look like?

A: Recovery from compassion fatigue is not linear, and doesn’t mean returning to your pre-caregiving baseline. You’ve had experiences that have changed you.

Typical timeline with consistent intervention: Weeks 1-2: Noticing patterns, naming what you’re experiencing, starting one boundary or self-care practice. You may not feel better yet, but you’re taking action.

Weeks 3-4: Initial therapy sessions beginning, implementing basic self-care routine, slight improvements in mood or irritability on good days. Bad days still happen frequently.

Months 2-3: More consistent emotional regulation, less persistent numbness, beginning to feel moments of joy or connection again. Physical symptoms may start improving.

Months 4-6: Restored emotional capacity to feel empathy without being overwhelmed, sustainable caregiving routines established, ability to set boundaries with less guilt, improved physical health markers.

Recovery looks like: You can emotionally engage with your loved one without absorbing their distress as your own; you have systems in place that prevent future burnout. You can advocate for your own needs without debilitating guilt. You recognize early warning signs when you’re approaching your limits.

You’ve accepted that “good enough” caregiving is sustainable while “perfect” caregiving leads to collapse. Recovery isn’t about eliminating all stress. It’s about building resilience and sustainability.

Q: Can I recover from compassion fatigue while still actively caregiving, or do I need to stop?

A: Most caregivers cannot simply stop caregiving, nor do they want to. You love this person and are committed to their care. The real question is not whether you can recover while caregiving (you can), but whether you can recover while caregiving in your current unsustainable way (you cannot).

Recovery while still providing care requires regular respite, firm boundaries around your time and emotional energy. It requires professional support to process trauma, a care team to share responsibilities, and practical solutions for overwhelming logistics like care coordination, finances, and managing providers. Some caregivers gain stability by arranging temporary increased support, such as having a family member stay for two weeks or using short-term facility respite.

This gives them the space to recover and set up sustainable systems. This isn’t giving up on caregiving; it’s recognizing that the current approach is harmful to everyone involved. Your loved one needs a healthy caregiver, not a martyr.

Special Circumstances

Q: Is compassion fatigue different when caring for someone with dementia or Alzheimer’s?

A: Caring for someone with progressive dementia creates unique compassion fatigue risks due to ongoing ambiguous loss. Grieving the person while they are still physically present is common. You may face anticipatory grief that intensifies daily as you witness their personality and memories fade.

Trauma from behavioral symptoms like aggression, accusations, or not recognizing you, and guilt for feeling relieved when they are calm or asleep. You might also experience identity confusion as your parent-child or spousal relationship fundamentally changes. Moral distress when making decisions they would have opposed if cognitively intact, and exhaustion from constant vigilance to prevent wandering or unsafe behaviors contribute to the emotions.

The repetitive nature of dementia care. That is, answering the same question dozens of times or having the same conversation repeatedly creates a particular type of psychological exhaustion. Additionally, you may experience disenfranchised grief.

Society doesn’t fully acknowledge your loss because the person is still alive, leaving you without the support that comes with recognized bereavement. Dementia caregivers need support groups specifically for memory care, not just general caregiver groups, as the psychological challenges are distinct.

Q: I’m caring for my spouse/partner. Our relationship has become entirely caregiver/care-recipient. How do I deal with this grief while still providing care?

A: The transformation of an intimate partnership into a caregiving relationship is one of the most painful aspects of spousal caregiving and creates specific compassion fatigue vulnerabilities. You’re navigating the loss of your romantic/sexual relationship and the loss of the partnership and teamwork you once shared. There is role confusion as you become both spouse and caregiver, resentment toward the illness (and sometimes toward your spouse) mixed with love, and grief that has no outlet.

You can’t fully mourn because the relationship isn’t “over,” and isolation as couple friends drift away because your social life has changed. This situation requires acknowledging multiple truths simultaneously. You can love your spouse deeply AND grieve the partnership you’ve lost.

You can be committed to their care AND need emotional intimacy that you’re no longer getting from them. You can honor your marriage vows AND need support from others, including potentially platonic relationships that provide emotional connection. Consider the Well Spouse Association, which specifically supports partners caring for chronically ill spouses, as well as therapy that addresses ambiguous loss and anticipatory grief. Have frank conversations with your spouse if they have capacity, about how to maintain a personal connection beyond caregiving tasks. Talk about permission to maintain aspects of your own identity and interests separate from caregiving. You’re not betraying your spouse by acknowledging this loss.

Q: I’m a long-distance caregiver and feel guilty that I’m not there doing more, but I also feel traumatized by what I see during visits. Is this still compassion fatigue?

A: Absolutely, long-distance caregivers experience compassion fatigue with the added burden of guilt, helplessness, and intense trauma during concentrated visits. You experience compressed trauma exposure (witnessing months of decline in a single weekend visit), hypervigilance from afar (constantly worried, waiting for crisis calls), and guilt about not being present physically. You may experience strained relationships with local siblings or hired caregivers, financial stress from travel and paying for services, and ambiguous grief as you miss day-to-day life while watching from a distance.

Additionally, you may experience caregiver imposter syndrome, feeling you’re not a “real” caregiver because you’re not there daily, even though the psychological burden is very real. The transition into and out of visits can be particularly traumatic. Seeing the decline all at once, racing to be present during crises, then returning to your regular life while emotionally devastated. Long-distance caregivers need therapy that validates the unique challenges of remote caregiving, technology to stay connected (video calls, monitoring systems) without hypervigilance. Coordination with your local care team helps. You need permission to set boundaries around how often you can visit or call, and recognition that you ARE a caregiver even from afar.

Q: I’m caring for a parent who was abusive or with whom I have a complicated relationship. Does compassion fatigue still apply, or is what I’m feeling different?

A: Caring for someone with whom you have a traumatic or complicated history creates an especially complex form of compassion fatigue layered with moral distress, old trauma being retriggered, and conflicted emotions. You may experience re-traumatization as old dynamics resurface when your parent becomes dependent. There can also be ambivalence about providing care—guilt about obligation versus resentment about their treatment of you.

You may feel unsupported by others who don’t understand your complicated feelings (“But she’s your mother!”). You might grieve the relationship you never had and find it difficult to access compassion when historical hurt is so present. This situation requires acknowledgment of several truths.

Providing basic care for someone doesn’t mean reconciling with past abuse. You can honor your values (compassion, responsibility) while still protecting yourself emotionally. Complicated grief and traumatic caregiver relationships are real and valid.

You may need firmer boundaries than other caregivers to protect your mental health. Consider therapy specifically addressing childhood trauma and its impact on current caregiving. Create very clear boundaries that prioritize your psychological safety. Explore whether alternative care arrangements (facility placement, another family member as primary) might be healthier. Release yourself from others’ expectations about forgiveness or reconciliation. You’re allowed to provide safe, adequate care without emotional closeness.

Looking Forward

Q: Once I recover from compassion fatigue, how do I prevent it from happening again?

A: Prevention requires maintaining the systems and boundaries you established during recovery. Compassion fatigue can recur if you slip back into unsustainable patterns.

Ongoing prevention strategies: Maintain regular respite, even when you feel fine. Prevention is easier than recovery. Keep boundaries strong and regularly check in with a therapist. Stay connected to your coach and caregiver support group for early warning signs and accountability.

Each week, rate your emotional well-being on a 1-10 scale, and have a plan for responding to early warning signs. Remind your other family members that sustainable caregiving requires ongoing, not just crisis, support. Allow yourself to adjust as your loved one’s needs change.

Compassion fatigue prevention is like maintaining physical health. You don’t stop healthy habits once you reach your goal. Finally, recognize that some caregiving situations worsen over time, so you may need to increase support even if you’re currently managing well.

Q: What if my loved one’s condition is terminal or progressively worsening? How do I prepare for the emotional impact while avoiding compassion fatigue?

A: Caring for someone with a terminal illness or progressive decline brings anticipatory grief and ongoing trauma, making proactive support essential. Waiting for a compassion fatigue crisis is not an option. Start by connecting early with hospice or palliative care teams.

They offer emotional support for caregivers as well as medical care for patients. Work with a therapist who understands terminal illness caregiving and create clear plans for who will support you during the dying process and afterward. Join support groups for caregivers of people with your loved one’s condition (cancer, ALS, Alzheimer’s, etc.), where others understand the journey and help you experience moments of joy and normalcy even as your loved one declines.

This isn’t disrespectful; it’s survival. Document positive memories now and have honest conversations (if possible) with your loved one about their wishes, including their hopes for your well-being after they are gone. Establish bereavement support before you need it.

Remember, witnessing the death of someone you love is traumatic, even when it is expected and peaceful. Arranging support in advance is not pessimism. It is wisdom.

Quick Reference: When to Seek Immediate Help

Seek emergency support (call 988 or go to ER) if experiencing:

- Active thoughts of harming yourself or your loved one

- Complete inability to function in basic daily activities for several days

- Substance abuse to the point of endangering yourself or your loved one

- Dissociation or feeling detached from reality

- Severe panic attacks that prevent caregiving

Seek professional support within 1 week if experiencing:

- Persistent emotional numbness lasting more than 2 weeks

- Intrusive thoughts/nightmares about your loved one’s suffering multiple times per week

- Complete social withdrawal for more than 2 weeks

- Physical symptoms significantly impacting your health

- Using substances (alcohol, food, medication) as your primary coping mechanism

Seek support when convenient if experiencing:

- Regular irritability/mood swings

- Difficulty sleeping 3+ nights per week

- Feeling resentful/emotionally disconnected from your loved one

- Physical exhaustion that doesn’t improve with rest

- Desire to understand and address compassion fatigue proactively

Remember: Seeking help for compassion fatigue isn’t a sign of weakness or failure as a caregiver. It’s a sign of wisdom and commitment to sustainable, quality care for your loved one.

Conclusion: You Can Not Pour From an Empty Cup

Compassion fatigue isn’t a character flaw; it’s a physiological response to prolonged exposure to suffering. The fact that you’re aware of experiencing it demonstrates your capacity for deep empathy and your commitment to caring for your loved one.

But here’s the truth that might be difficult to hear. If you continue your current path without intervention, you will not be able to continue caregiving. Burnout isn’t a possibility; it’s inevitable.

The most loving thing you can do for the person you’re caring for is to care for yourself. Not someday. Not when things calm down. Now. Your mental health matters. Your physical health matters. Your capacity for joy and connection matters. You matter, not because of what you do, but because of who you are.

Start with one small step today. One boundary. One self-care practice. One phone call for support. That’s all recovery requires, one small step, followed by another, and another.

You don’t have to do this alone. And you deserve the same compassion you’ve been offering to others.

Resources:

- National Alliance for Caregiving: caregiver.org

- Family Caregiver Alliance: caregiver.org

- ARCH National Respite Network: archrespite.org

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

- CoachLandry, LLC: www.coachlandry.com

This blog’s tone is intended to be direct, compassionate, and focused on practical solutions rather than just information. It acknowledges the reader’s pain while offering genuine pathways forward.